This apparently ‘magical’ device is far from new. At first it seems counter-intuitive, but how a heat pump works actually makes sense given a little thought

See my Youtube video

HOW CAN HEAT BE EXTRACTED FROM COLD WATER?

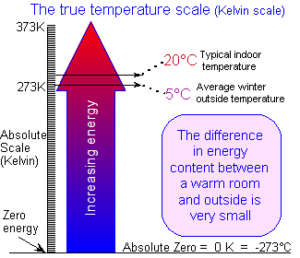

Our natural sense of heat is based more on instinct than on science. Humans are warm-blooded and judge “heat” by comparing it by touch. Since our body temperatures need to be maintained within a few degrees for survival, our natural senses have evolved to make extremes of temperature uncomfortable. To us, a hot summer’s day feels many times “hotter” than the freezing mid-winter. But in reality the Earth’s surface does not vary in “heat energy” as much as we might imagine. Scientifically speaking, there is only 11% less energy in cold river water at 5°C (40°F) than in hot bath water at 40°C (105°F). (In Absolute terms, this is 278 and 313 degrees Kelvin)

Once we appreciate this more accurate understanding of the heat content of our surroundings, the idea of extracting heat from something that instinctively appears to be cold, should be less perplexing.

The most familiar form of heat pump is the domestic refrigerator. Here, heat is extracted from the cabinet to keep food fresh and the extracted heat is expelled through the grill at the back of the unit. In this case the heat is merely a waste product. With a heat pump (for heating), we utilise this heat, and put the “cold part” outside.

To make this more understandable, let’s imagine that the “ice box” of your refrigerator is placed outdoors, and exposed to the outside air, and the hot grid from the back is kept inside a house. The “ice box” will attempt to cool down the outdoors, but the outdoors is so enormous that, extract as it will, the outside does not cool down. In this example, heat energy is being continuously extracted from the outside air. Energy cannot disappear, and has to go somewhere. The extracted energy ends up as heat in the warm grill (from the back of the fridge), available to heat the house. In every case, the useful heat delivered to the house will be greater than the energy required (electrical) to run the mechanism. (the houses gains heat, the outside looses heat).

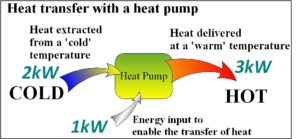

The principle of the heat pump can be hard to grasp at first since it is not an immediately obvious process. The diagram below may help the penny drop. You should note that this ‘uphill’ (from cold to hot) heat transfer process requires an energy input… it is not free to operate, but the total useful heat energy delivered can be several times the electrical energy input to run the system.

In this example, the 1kW power input is used to extract 2kW from outdoors. These two energy inputs end up in the house and total 3kW of heat.

Below is another way of thinking about the concept. The temperature of any material relates to vibration of the tiny molecules that it is made of. The hotter something is, the faster the molecules vibrate. In the animation below, we can see a ground source system. Here, the molecules in the house are being speeded up due to the ground molecules slowing down. Energy has not been created or destroyed; it is simply transferred from one place to another.

The specific details of the inner workings of a heat pump are not dealt with here, but if you are intrigued …. they involve the evaporation and condensation of a working fluid called the Refrigerant. In brief, on the ‘cold’ side of the heat pump is the evaporator. In here, the refrigerant evaporates under low pressure. On the ‘hot’ side of the system is the condenser. This is at a high pressure, and the refrigerant is ‘forced’ to condense. Coupling these two items is a compressor which maintains the pressure difference between the two sides. A flow control device (often called an expansion valve) allows condensed liquid to run back to the evaporator to complete the cycle.