(Note- if you are reading this.. you might also be interested in my new flow and pressure simulator)

“What is the point of having a large diameter pipe run when the fittings on the heat pump are small?”

I have heard that statement enough times to make me want to write a blog about it.

It seems intuitive to think that any bottle neck in a pipe system is the limiting factor for the flow–rate. At first thought, it seems like the ‘weakest link’ in the system. I then started to wonder why this topic is so well understood by electricians and so misunderstood by some plumbers.

I also recall chatting to a Heating College lecturer who said “They have made these training courses so you don’t need to think anymore”. If that is the case no wonder the topic can be perplexing. However, it is far from rocket science.

So a little thinking …

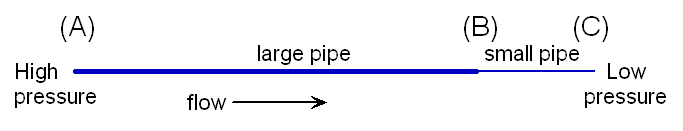

For water to flow through a pipe system, a pressure difference is required. [between (A) and (C)]. This pressure is usually provided by a circulation pump that literally pushes the water through.

The flow-rate depends on two things, 1) the pressure difference between (A) and (C), and 2) the total restriction of the pipe.

The flow-rate depends on two things, 1) the pressure difference between (A) and (C), and 2) the total restriction of the pipe.

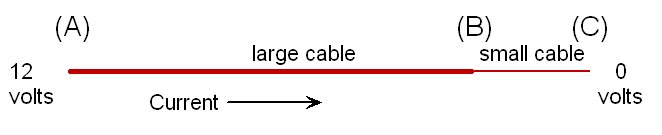

Electrical circuits are almost the same.

In electrical terms, we have Voltage (the pressure), current[amps] (the flow-rate), and total resistance[ohms] (the restriction of pipe circuit)

Every electrician knows Ohms law intuitively –

Every electrician knows Ohms law intuitively –

v = i multiplied by r or volt difference = amps x resistance[ohms].

However, heating does not have a commonly known equivalent

e.g. pressure difference = flow-rate x restriction

The reason why electricians have it so sussed is that they have the tools to know exactly what is going on in every circuit. A volt meter can show the voltages at all points in a circuit. A current clamp can show the amps that are flowing. We can easily know exactly what is going on in any cable.(e.g the voltages at points A,B & C)

Plumbers have no such luxury. We would need tapping ports at various points around a circuit if we want to know pressure differences. We only know the static pressure at one point, which tells us nothing. Furthermore, we generally have no idea how much is flowing in each individual pipe run. There is also no easy way of measuring the resistance of a pipe system, so there is no easy resistance equivalent for pipes and fittings. All-in-all, the heating engineer is very much in the dark, and would have little idea what the pressure is at point (B).

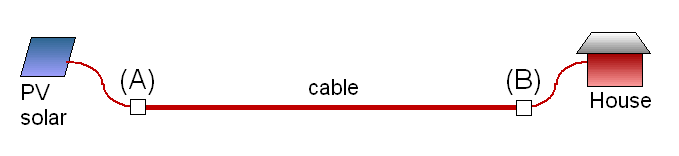

Now let’s consider a simplified scenario that an electrician might face –

Here we have a PV panel at a long distance from a house. It will make perfect sense to any electrician to have a very thick long cable from (A) to (B), whilst having relatively thin cables at each end. The important requirement here is that the total volt-drop due to total cable resistance is kept low. For every metre of cable, there is a very small volt drop, and all these add together. The calculations can easily show the volt-drop. You can use a cable calculator on-line.

Here we have a PV panel at a long distance from a house. It will make perfect sense to any electrician to have a very thick long cable from (A) to (B), whilst having relatively thin cables at each end. The important requirement here is that the total volt-drop due to total cable resistance is kept low. For every metre of cable, there is a very small volt drop, and all these add together. The calculations can easily show the volt-drop. You can use a cable calculator on-line.

It is the LENGTH here that is the issue. If (A) and (B) are close, that section could be thin, but if the cable is long, it need to be fat. If the cable is very long, it needs to be very fat. However, making the short ends any fatter will make very little difference to the total volt drop.

Back to our water pipes,

The same thing applies. Every metre of pipe causes a pressure drop (when water is flowing), and every metre adds up. Again, it is the LENGTH that is a major issue here. For example, if you have say a 5m length of pipe and you need 1m head of water (0.1 bar) to make a certain flow rate, then you need twice the pressure if you have twice the length. 50M of pipe would need 10m head (1 bar) to give you the same flow rate. However, it you swap that 50m long pipe for one of bigger diameter, you will have far less ‘resistance’ in the pipe. The required flow rate can be achieved with far less pressure.

You can play with an on-line calculator to see what happens with different pipe sizes and lengths. See http://www.pressure-drop.com/Online-Calculator/

It is easy to overlook the pipe LENGTH, this has just as much affect on the flow and pressure drop as the diameter does. This is why a water meter with a very small bore does not affect the flow-rate very much – it is very short. Put 10 water meters in-line, one after another, and you have a big restriction, and a big problem.

So, back to our earlier assertion that any small-bore section of pipe bottleneck is akin to the weakest link; The bottle-neck principle does not apply here in the same was as it would to traffic on a motorway. If cars acted like water molecules or like electrons, they would push bumper to bumper and shoot through a bottle-neck at extremely high speed!

I have added a page on this topic here http://heatpumps.co.uk/technical/pressure-drops-flow-rates/

An example

To finish, let’s do a little exercise on pipe sizing. Let’s look at a scenario with a 10m (30ft) high header tank is supplying a tap/valve via a large bore pipe. i.e. a good 1 bar pressure supply of water. Let’s consider extending this pipe horizontally and look at what flow-rate will emerge out the end of it. We are assuming 1 bar pressure at the start, and zero bar (atmospheric pressure) at the outlet.

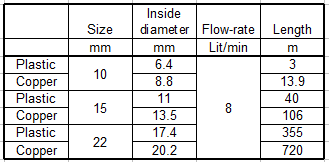

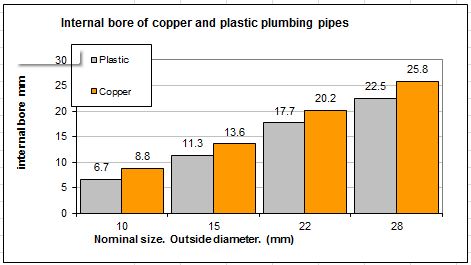

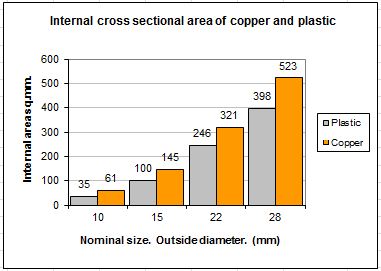

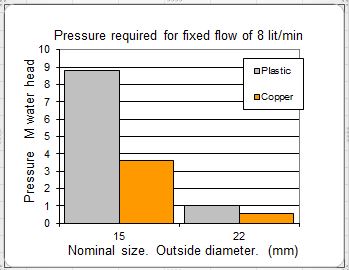

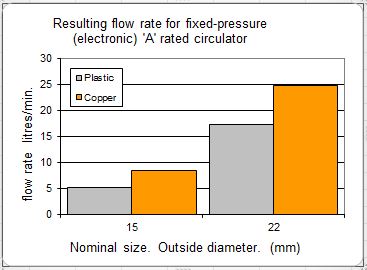

We can firstly consider a 15mm (outside diameter) pipe (the most common pipe size for taps).

One 40m length of this plastic pipe would give us a flow rate of around 8litres/minute (About 2.1 US gallons/min or 1.75 UK gal/min.). This is a typical bath-tap flow rate.

If we use copper instead, the wall-thickness is thinner and internal bore is bigger. We could have well over twice the length of pipe and get a similar flow rate coming out of the end.

As you can see from the grid, you could go as far as 720m if a 22mm copper pipe were chosen.

If we go in the other direction and fit a small pipe, we can see that a 10mm copper micro-bore pipe that was about 14m long would still give us 8lit/min. If we now look at 10mm plastic with its small internal bore of only 6.6mm (pencils are fatter than that) then it could be no longer than 3m if we want the same flow rate to fill a bath.

This simply illustrates how the diameter and length could be adjusted to give the required flow rate given a certain available pressure. In summary, a short thin pipe may act similarly to a long fat one.

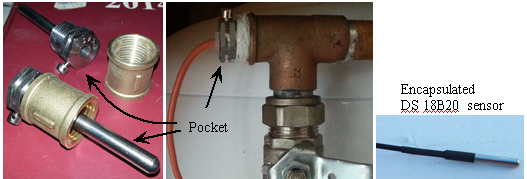

They actually have 3 connections; 0v, 5v and signal. Since each sensor has its own unique i.d. code, multiple sensors are simply connected into the same 3 terminals on the monitor device.

They actually have 3 connections; 0v, 5v and signal. Since each sensor has its own unique i.d. code, multiple sensors are simply connected into the same 3 terminals on the monitor device.

The picture shows the compressor with strap-around element heaters. The compressor was quite warm, but one wonders why the lagging around the shell was open at the top; possibly to aid compressor cooling for times when the compressor is working at it’s upper temperature limits?

The picture shows the compressor with strap-around element heaters. The compressor was quite warm, but one wonders why the lagging around the shell was open at the top; possibly to aid compressor cooling for times when the compressor is working at it’s upper temperature limits?